I'm starting to work on my new project, Digging Down: Fragmented Totalities, supported in its initial R&D phase by National Theatre Wales' Waleslab. The project will make use of found fragments and objects, the things that we find and collect, but are not quite sure why. Stimulated by the questions raised by a horde of objects I have dug from my garden in Nantperis, I will be collaborating with others to develop a Last Supper, as an immersive experience in which to eat, talk and explore the potential of the fragment as a way of understanding ourselves, our relationships, the universe and everything.

Its exciting to get going on the project, and I've got so many (too many?) ideas. So I’ve produced this ‘primer’ to try to pull some background information and ideas together, as a first step to engaging with others. Because after all, this project is the first one that I am building collaboration with others in right from the start.

This is my first ever blog, so I'm sure there is room for improvement. All thoughts, involvement, ideas welcome!

First of all, a little about the structure of the Waleslab supported R&D phase of the project

January 2015 Develop initial ideas, background research (including this primer). Attend Waleslab's launch meeting with other Waleslab creatives (21 Jan), pull together ideas sufficiently to identify potential collaborators

Feb/March Engage with other artists, creatives, archaeologists, curators, local people to develop props and ideas to take to the development week. I'll also attend the Assembly preparation week in South Wales (9-13 March) to find out how NTW go about preparing for an event - how they combine performance with debate. I also want to send out invitations to sharing ‘last supper’ event participants (hold the space in diaries).

April (ish) Hold a development week, with 2 collaborators, leading up to a sharing event at the end of the week. Sharing event to be in the form of a ‘last supper’ that will give participants an opportunity to experience elements of the R&D phase, and to discuss potential for next steps.

Before I go any further, I should probably say a little about the definitions of things I'm going to be working with:

Fragment: A part broken off or otherwise detached from a whole; a broken piece; a(comparatively) small detached portion of anything; An extant portion of a writing or composition which as a whole is lost; a portion of work left uncompleted by its author; a part of any unfinished whole or uncompleted design.

Fragment n (‘fraegment). 1. A piece broken off or detached: fragments of rock. 2. An incomplete piece; portion: fragments or a novel. 3. A scrap; morsel; bit – vb. (fraeg’ment).

Found Object: Objet trouve (not particularly helpful)

Found Object: A natural object or an artifact not originally intended as art, found and considered to have aesthetic value.

Why the Fragment?

“In a universe thus fragmented, there is no logos which gathers up the pieces”

Raymond Pettibon

Ever since I remember, I’ve gathered fragments – from my first ‘sucky’, a fragment of a pyjama leg (that embarrassingly, I slept with until I was in my twenties), to rocks and fossils and clay pipes, pebble and shells to bits of insects, snippets of songs and fragments of rocksalt found on the road to ticket stubs and Nana’s old carpet.

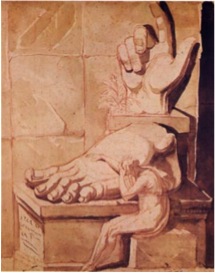

So I was in ecstasy when I moved to my house in Nantperis in 2005 and discovered that the crumbling, steeply terraced garden was flooded with fragments. Pottery, glass, metal, leather, wood, burnt embers, bone, rock, slate flowed in their hundreds – thousands even - down hill. New specimens emerging with every rain shower, every soil slip, every next crumbling of the terraces. From the initial delight, the sheer volume of it all started to make me feel a little like Fuseli’s ‘Artist Overwhelmed by the Grandeur of Antique Ruins’. What was I to do with it all? How could I do justice to it, make sense of it? There was a tension between being drawn to the specialness of the individual fragment, and to facing up to the sheer remarkable volume of them, of variations and collections and a need to store and manage them. I needed help, and that’s what this project is all about.

Things I’d like to include or explore in the Waleslab R&D phase of the project

In this R&D phase I want to stop and think about why I am compelled to gather these things. Do other people do the same? What is the potential of using these fragments and objects as a way of engaging with others to dig down into the meaning of life, the universe and everything?

I’ve started to identify possible lines of enquiry that we could pursue.

Fragments as process and connection: ‘represencing’

My first question is whether (and if so why is) there is solace in finding (and especially perhaps, digging up) fragments and objects? Perhaps they provide a connection to the past and to the future, anchoring our place within his(hers)tory? Perhaps they offer us something to cling to, a bit like an island in the storm. A coping mechanism. Maybe it is a variation on the cult of the relic, the creation and distribution of body fragments as holy objects.

And of course we are talking of fragments rather than a whole. Perhaps there is something in the divided, fragmented self that relates to the fragmentation and finds comfort and affirmation in it.. Maybe it is a relief not to have to deal with the whole? The whole can be complicated, may contain good and bad, whereas the fragment seems to just bring out the promise – or the memory – of the best, of ourselves, of others.

After all, perhaps this is what we are doing on social media: carefully presented fragments (of a hidden whole) to ‘represence’ ourselves for others. This re-presencing has a long, long tradition, going right back to Neolithic times when objects were exchanged and fragments dispersed as a way of maintaining social relations.

The perfect fragment

I am somewhat attached to the notion of ‘a perfect fragment’, something that as the romanticist Friedrich Schelgel might describe as “a fragment, like a minature work of art, has to be entirely isolated from the surrounding world and be complete in itself like a hedgehog”? Is there one piece that would be so special, I would give up all others to keep it, and why? Why do I pick up a particular pebble on a beach? What does it say about me? What would others’ perfect fragments say about them? There is something about discovering a fragment, or a found object, which is about the relationship being first and foremost with the finder’s own subjectivity. Perhaps it triggers a jolt of recognition. Like a fetish, it fills a void, like finding the right word within a poem, offering a vehicle for meaning. This would be as true of a fragment of poetry or writing or a song or music as it would of a physical thing.

Universal fragmentation

Cold Dark Matter: An Exploded View. Cornelia Parker 1991

But then, (my thinking process mirroring the evolution of thinking about the fragment), as Freud, Lacan, Derrida and the like might say (here in the worlds of David Bohm), “There is not, and cannot be any escape from fragmentation as it is the one thing in life that is universal”. The volume of the fragments and objects that I’ve found, the sheer unstoppable flow of them down hill does seem significant. They collectively embody the inevitable fragmentation and dismemberment of that transitory state ‘wholeness’.

As Rebecca Solnit says: “Every object is afloat on the processes that created it, and will consume it. They tell their stories in a language older than image-making or speaking”. Perhaps we like fragments because act as reminders or signs as to the absent, as well as being things that exist and have meaning in their own right. They naturally evoke stories.

The compulsion to piece together

One of the most striking reactions of people to the fragments and objects that I’ve gathered - first brought to my attention by my tutor Jony Easterby - is the compulsion to piece them together. Seeing fragments (especially many similar, related looking fragments) together give a very strong feeling that they (we?) are desperately incomplete. It makes us feel good to complete them. But once complete, do they lose their interest? It is the missing pieces that confer on the surviving pieces their status as fragments, and is this fundamental to their intrigue?

Maybe so, but this same compulsion led me to start to piece together information about where the fragments came from. Who might have thrown them away, when? As Will Viney says: “Asking what waste is for me is to ask how its relation to ‘someone’ has been done and undone over time”.

So what might the lives of those that threw away this waste, these fragments and objects, have been like? Last week I started looking at census records (exciting, all that microfiche in the record office) to find out about the history of our house and its previous inhabitants. So many confusing fragments of information! Today I went to the Nantperis graveyard to try to make more sense of it, and found graves of the Griffiths family that first occupied this house from the 1870s. They lived here for more than 20 years, and I believe they were the people whose waste I've been digging. There is a thrill in the connection! In piecing together the fragments. Perhaps the fragments of sculpted slate (of a type more usually found in the Ogwen valley rather than this one) were made by Griffith Williams who lived until at least 84 years old? While living here, Ellen Williams, his daughter in law lost a baby (also called Griffith) of 3 months, and then her husband (Owen), and his brother Robert in the quarries. But she had two other sons - also quarrymen - who survived. Are those toys that I've found - the gun, the metal animals - what her sons, Humphrey and Owen used to play with?

On rubbish and waste

“I’d like to suggest to you that one of the peculiar characteristics of things that we call ‘waste’ is their strange suggestibility, their enigmatic power to pose questions whose attending answers in the end, feel rather excessive, superfluous or insufficient… it has entered a peculiar form of time, one that emerges out of its status as a ‘has-been’, a remainder or trace of action whose relation to the past is suspended in its presence… a universe of matter that swirls in and through us” Will Viney.

Will Viney writes so eloquently on waste, and reflects much better than I ever could on the matter, I won’t try to say more on his thoughts here. But I hope that in this project, we might explore some of those questions and answers that he refers to. In the meantime, you can read more of his thoughts here: https://narratingwaste.wordpress.com/about/

Slightly less eruditely, the sheer volume of waste (the fragments and objects I’ve found in the garden) also raises with me the issue sustainability, and in particular of consumption. It makes me not only think about levels of consumption (of things, food, medicine) in the past, compared to ours now (think of what our middens would be like, what they’d compose of if we were to dispose of our rubbish in our gardens), but also of how I am unable to say to myself ‘how much is enough’ in terms of gathering in the fragments and objects. I just can’t stop! I’ve even made a video of it:

That's it for now: the next post will be about my ideas for installation and performance, and the sharing at a last supper....